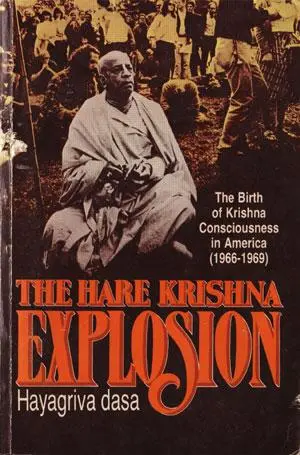

The Hare Krishna Explosion

by Hayagriva das

Part III: New Vrindaban, 1968-1969

Chapter 16

Krishna, The Flower-bearing Spring

I return to West Virginia in time for a major snowstorm. Aghasura Road becomes a shimmering white path through a fantasy land of icicles. In the little farmhouse, nucleus of our transcendental village, it is impossible to keep warm. Cold air somehow seeps through the old floorboards and cuts through cracks. We stoke the woodfire in the steel oil drum. At night, the oil drum glows crimson, like a self-contained galaxy in the dark blue cold of space.

We are spared the worst northwest winds sweeping down from the Arctic and Canada, and across the plains from northern Ohio, for our wise pioneers built the little house on the eastern side of Govardhan Hill. Still, the sun rises late, reluctantly. We sit two hours in the predawn darkness, chanting aratik mantras, reading Bhagavad-gita, and stoking the fire. There are always logs to cut, brambles to break, firewood to haul in to dry before burning.

The predawn hours are the coldest. We stand wrapped in blankets before the little altar as Kirtanananda offers incense, camphor, ghee, water, handkerchief, flower, peacock fan, and yak-tail whisk to the Radha Krishna and Jagannatha Deities.

“When making aratik offerings,” he writes Prabhupada, “is it proper to meditate on the different parts of the Lord’s body?”

Prabhupada writes back no. “The Lord is actually there with you,” he replies. “And you are seeing all of His bodily features, so there’s no need to meditate that way. Food should be offered before aratik…”

Of course, this means getting up earlier to cook. We take turns tending the fire. I don’t thaw out until I’m in my office in Columbus.

At the university, interest in the O.S.U. Yoga Society increases.

I offer a supplemental course at the Free University. In my eagerness, I get a reprimand from the English Department chairman, who catches me mimeographing Yoga Society handouts.

I quickly offer to pay for paper and ink, but the damage has been done. I begin to wonder about my contract renewal.

“Don’t be anxious whether you are fired from your present service or not,” Prabhupada writes. “Don’t do anything that will unnecessarily disturb the authorities, but in all circumstances execute this Krishna consciousness program, even at the risk of dissatisfying your so-called employer master.”

A department colleague informs me that Allen Ginsberg is scheduled to give a poetry reading sometime in May. He’s been contracted by the Student Union in what students consider a rebellious gesture against a staid O.S.U. administration.

I write Allen at his upstate New York farm and ask if he would be interested in chanting with us at a campus program.

“I have a date at O.S.U. for May 13,” he replies, “and yes we should have a sankirtan hour there.”

Prabhupada tells me that I should arrange his arrival in May to correspond with Ginsberg. “I’m so glad to learn that Mr. Ginsberg is taking some serious interest in our Hare Krishna movement,” he writes. “When he actually comes into Krishna consciousness, which I expect will be in the very near future, our movement will get a great impetus.”

At New Vrindaban, we are enlivened by thoughts of a mid-May visit by Prabhupada. We wait like spring buds buried beneath snow, just enduring the cold, knowing that the day will come when the ground thaws, and the sun will resurrect us.

Wheeling Electric chainsaws a swath from the ridge road down to the creek and up to our farmhouse—a mile and a half—throws up poles, and strings cable across the creek. “Let there be light!” For the first time in history, electricity lights New Vrindaban.

No more temperamental Coleman lanterns. No more flammable kerosene lamps. No more squinting to read Bhagavad-gita in the early mornings.

“They have finally installed the electricity,” I write Prabhupada happily. “And it makes all the difference here. At last we can begin to make some progress.”

“Progress” is a very sunny word to use, however. Though the electricity helps in many ways, we still sit frozen and landlocked. Half the day is spent gathering wood to burn and bringing up supplies. With the powerwagon dead beside the creek, we have to walk everything up in the snow and ice, or (worse) mud and cold rain. And supplies are inevitably bulky and heavy—twenty-five pounds of sugar, cooking oil, cartons of powdered milk, mung beans, flour. Determined, we endure those frozen treks. Our back packs bulging, we walk the two miles in night blizzards even, hoping to reach the house before flashlight batteries run down.

The timid sun rises late and dim, stays low in the sky, usually behind clouds, and vanishes mysteriously around four in the afternoon. Trudging up and down Aghasura Road, we often wonder, Why here? Why not on warm Hawaiian beaches? Or California?

Prabhupada’s letters goad us on:

“The immediate necessity is to construct some simple cottages for living purposes…. Another important scheme is to start a nice printing press next spring. We have so many books to print…. Now you must construct seven temples as in old Vrindaban…. We must have a school and qualified teachers for the children…. What progress have you made on living accomodations? Many devotees are ready to go there immediately. Everything appears very bright for the future. We just have to work very sagaciously and success will surely be there…. Press or no press, we must have some houses there because many students are eager to go….”

In the helplessness of our situation, Prabhupada’s utopian requests keep us splitting firewood and hauling supplies up and down Aghasura. After all, a brief four centuries ago, only a few humble wigwams dotted the island of Manahattan.

Still, to us, the idea of a community seems an impossible dream. We see ourselves more often as four outcasts living in a shack. Only Prabhupada’s letters hint at more. Only he can truly envision a transcendental village.

Now Bhagavad-gita As It Is is receiving some appreciation.

“The book is without a doubt the best presentation so far to the Western public of the teachings of Lord Krishna,” Prabhupada quotes Dr. Haridas Choudhary of the Indian embassy in San Francisco.

“Now we must make propaganda to convince the colleges to present it to their students. I am happy to hear that you are selling some fifty Gitas weekly and that your Lord Chaitanya play is at last completed. It is very well done, simply a little prolonged. In London, Mukunda is ready to print a new edited version of ‘Easy Journey To Other Planets.’ I hope that soon Brahmananda will get our own press so we can print these books. Macmillan deletes so much that it is not possible. We shall have to publish on our own press….”

As March roars in with blasts of Arctic air, we are still landlocked, vehicles still sit in the creek graveyard, and Aghasura Road remains impassable as ever. Despite Prabhupada’s encouraging letters, we feel ourselves the snail of ISKCON. From London, we hear that Shyamasundar and Mukunda are going to cut a Hare Krishna record with George Harrison and John Lennon. If the Beatles chant Hare Krishna, millions will hear.

From our new Oahu center in warm Hawaii, Prabhupada writes:

“The boys and girls in London are doing very nicely. My Guru Maharaj sent one sannyasi, Bon Maharaj, to preach in London in 1933. Although he tried for three years at the expense of my Guru Maharaj, he could not do any appreciable work. So Guru Maharaj, being disgusted, called him back. In comparison, our six young boys and girls are neither Vedantists nor sannyasis, but they are doing more tangible work. This confirms Lord Chaitanya’s statement that anyone can preach provided he knows the science of Krishna.”

New centers also open in Vancouver, Hamburg, Kyoto, Berkeley, Laguna Beach, Boulder, Detroit, Buffalo, Philadelphia, Washington D.C. On travelling sankirtan, Kirtanananda goes to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and interests students there. In Columbus, I pressure Pradyumna to find a place near campus where students can visit daily. Our two-room apartment on High Street is inadequate. When Prabhupada arrives in May, we must have a temple ready.

As our May meeting at the University approaches, Allen Ginsberg expresses some concern, writing:

“Though I’m glad to chant with Swamiji, I’m not sure that a mixture of his presence and my poems will be appropriate. He may be offended by the poetry, or it may seem inappropriate to his teachings, which are more detached from sexuality and other worldly politics that I am into. On the other hand, I don’t think he’s ever heard me read, and that would be interesting too.”

We agree that this might be inappropriate. Best chant on a different night.

“I don’t want to wish on him a situation where he’s a captive audience to my stream of consciousness or my notoriety,” Allen adds. “You might consult him on the proprieties.”

From Hawaii, Prabhupada writes that he will arrive in Columbus on May 9 and that he can chant with Allen any day thereafter. At last! A specific date! If Allen’s poetry reading is on May 13, we can schedule a massive “chant-in” for May 12. Ranadhir begins drawing up posters.

“For your toothache trouble,” Prabhupada writes Kirtanananda, “mix common salt, one part, and pure mustard oil, enough to make a suitable paste. With this brush your teeth, especially the painful part, very nicely. Gargle in hot water, and always keep some cloves in your mouth. You don’t have to have your teeth extracted….”

“You may not put the initiation beads on the cow,” he writes my wife. I am perplexed, for as yet we have no cow.

“Nor is it necessary to recite the Gayatri mantra aloud,” he adds. “It should be silent or whispered.”

To me: “Husband and wife should chant at least fifty rounds before going to sex. The recommended period is six days after the menstrual period.”

To Kirtanananda: “Delivering children is not a sannyasi’s business. You should not bother about it. Best thing is that the women at New Vrindaban go to a bona fide physician.” But no one’s pregnant!

Reg Dunbar at the Goat Farm presents us with thirty quarts of pickled cucumbers. Kirtanananda asks Prabhupada about them, and from Hawaii comes the hurried reply:

“So for the cucumber pickles: We should not offer to the Deity food prepared by nondevotees. Aside from this, vinegar is not good. It is tamasic, in the mode of darkness, nasty food. So I think we shall not accept these pickles.”

Kirtanananda empties all the pickles out of the Mason quart jars, then scours the jars with soap and hot water.

“I think it is not proper for Srimati Radharani to have a white night dress,” Prabhupada writes.

Kirtanananda buys new night clothes for the Deity. Dark blue. Gold. Beige. Pink.

“I do not understand why you still have no cows,” another letter states. “New Vrindaban without cows does not look good.”

George Henderson, now teaching mathematics at Rutgers, visits for a couple of days. Laughing, he recalls the time Prabhupada challenged him to display the universal form. When he leaves, he gives us a check for two hundred dollars. “Buy that cow,” he says.

When Prabhupada wants a cow, Lord Krishna dictates to random souls to give in charity. And when the cow needs a cowherdsman, Lord Krishna, directing the wanderings of all living beings, sends us Paramananda and his wife Satyabhama.

Before coming to Krishna consciousness, Paramananda and Satyabhama lived at Millbrook, New York, at the community founded by Timothy Leary and his psychedelic clan. After initiation by Prabhupada, they moved to an apartment near Matchless Gifts. As soon as they heard of New Vrindaban, they decided they had to try it. “Go there and help,” Prabhupada told them. “Chant and be happy.”

Now, in the cold March wind, Paramananda clears bottles and garbage out of the shabby chicken coop, cuts out windows, staples plastic over the openings, and installs an oil barrel for heating. Within an afternoon, he converts the small chicken coop into a liveable dwelling and unceremoniously moves in with Satyabhama and a few boxes of books and clothes.

Satyabhama wants to teach children and cook. Paramananda is eager to raise cows and farm. He feels that the solution to Aghasura Road is simple.

“What you need, “ he tells me, “is a wagon and two workhorses.”

With hopeful know-how, he explains how he can harness the horses to a four-wheel wagon and bring supplies up and down the road all year, in rain, mud, ice, snow, whatever nature throws our way.

I consult Kirtanananda and Ranandhir. We all agree. Paramananda has been sent by Krishna to tend cows and conquer Aghasura. Of all of us, Paramananda is the calmest and most practical, a real man of the soil. We send him off to farm auctions to search for wagons and horses destined for the glue factory.

After repairing the pasture fence, we buy our first cow, named Kaliya by Prabhupada, a seven-year-old cow that has just lost her calf. Part Jersey and part Holstein, black with a white stripe down her nose, Kaliya is a gentle soul. She is fed by Ranandhir, milked by Paramananda, and garlanded by Satyabhama. Her big, brown, tranquil eyes tell us that she appreciates being protected from slaughter houses. Happily, her milk is rich and plentiful.

The more we battle with Aghasura, the more we realize how much simpler our lives would be on the ridge road, and we desperately try to buy property from our two neighbors, Mr. Cooke and Mr. Thompson.

Mr. Thompson owns the two farms adjacent to us, some three hundred acres of choice property on the ridge top. Due to his farms, we are forced to use Aghasura Road. Occasionally, with Mr. Thompson’s permission, we use the ridge top and drive right across to Vrindaban. Compared to Aghasura, the ridge top is a modern freeway.

We don’t ask permission too often, for everyone knows that with repeated use, we can establish right of way. Mr. Thompson is a considerate neighbor, but everyone has his limits. When asked if he’s interested in selling, he says, “Maybe. If I can get a good price.” I ask what this might be, and he says, “Twenty thousand or so.” The subject is dropped. The figure seems astronomical to us.

In Columbus, Pradyumna’s house hunting has succeeded. The house is made to order. Only three blocks from campus, it stands on the fringe of Greek-columned fraternity row. A large, three-story wooden house, it can serve adequately for a temple and living quarters.

We quickly sign a year’s lease and pay a deposit and $175 for the first month’s rent. The landlady is most amiable. She tells us that we can move in tomorrow.

Aham ritunam kusumakarah: “And of seasons, I am flower-bearing spring,” Lord Krishna tells Arjuna.

And truly a reminder of Krishna, our first spring at New Vrindaban! First, the light green buds on the willow beside the old house appear. Then the Appalachian grass, the pungent onion grass, the green umbrellas of May apples, dandelions, and blankets of violets spread up and down the creek hollows. With the sun’s return come warmer and longer days, the fading of the dull browns of winter, the greening of rolling hills, awakened hornets and flies, scurrying groundhogs, busy, talkative birds, the fresh smell of newly plowed earth.

Doors are unnailed, plastic torn off windows, the indoors emptied outdoors to bask in the purifying sun, the rooms swept and cleansed with disinfectant, floors repainted, walls whitewashed. Kirtanananda inspires the brahmacharis to live ascetically in the pigpen or barn, or in a lean-to on the hillside. Building supplies arrive, Ranandhir driving them up in the resurrected powerwagon, and Paramananda and the horses rattle up and down Aghasura Road, covered with mud, the sugar no doubt wet, the butter melted. Now at last we feel we’ve the upper hand of Aghasura, despite the spring rains and ever deepening ruts. Occasionally the powerwagon gets stuck, or the wagon breaks, and Paramananda and Ranandhir arrive later and muddier than usual, but they arrive. We are learning to take obstacles in stride.

“O Arjuna, the nonpermanent appearance of happiness and distress, and their disappearance in due course, are like the appearance and disappearance of winter and summer seasons. They arise from sense perception, and one must learn to tolerate them without being disturbed.”

Vamandev begins repairing the upstairs quarters in the old farm house for Prabhupada. He puts up new plasterboard, lays linoleum, paints the walls and ceiling. Prabhupada’s personal servants—Purushottam and Devananda—can live below and walk up the narrow stairs to serve him. Prabhupada’s Deities can reside in the small upstairs room partitioned off by cherry paneling. Prabhupada can sit and contemplate his Deities, or look at the garden and willow outside. Already no one can deny that New Vrindaban has atmosphere. With satisfaction, we imagine Prabhupada’s happiness—”I will forget to return to the old Vrindaban….”

From Hawaii, Prabhupada flies to Los Angeles, thence to New York and Boston, where Satsvarupa has been trying to acquire a press.

“Have you bought the adjacent land yet?” Prabhupada asks via Purushottam. And we sadly have to say no.

“Perhaps I shall go to Chapel Hill, North Carolina,” he writes, “and from there to Columbus and then to New Vrindaban, if it is possible, and stay there for as long as you like.”

Last minute changes of plans, flight cancellations. Prabhupada doesn’t have time to go to North Carolina and still attend the Ginsberg engagement May 12. North Carolina is sacrificed. He flies directly from New York to Columbus.

We gather before the arrival gates some thirty minutes before the plane lands. Surprisingly, about two hundred students from the university show up. There are also three devotee sankirtan parties—from New Vrindaban, Washington, and Buffalo. At the request of airport officials, we delay chanting, but as soon as the plane taxis into view, Hare Krishna begins.

Jai Sri Krishna! At last Prabhupada has arrived!

Devotees jump atop chairs to see. The students press forward to the protective glass windows through which we can watch the passengers deplane.

As usual, Prabhupada is the last to emerge. Some devotees begin throwing flowers. Then, as he enters the gate, we all offer obeisances, falling to the floor.

When we look up, we see Prabhupada standing before us, radiant, healthier, and stronger than we’ve ever seen him. He’s obviously delighted to see so many students come to greet him.

Kirtanananda garlands him first with a string of marigolds.

“Ah, very nice,” Prabhupada says. Then, looking at me: “Hayagriva Prabhu.” I approach him, bow to the floor again, recite the mantra of obeisance, touch his lotus feet, and feel his hand patting the top of my head. Yes, His Divine Grace is pleased.

Damodar from Washington and Rupanuga from Buffalo also garland him, this time with roses and gardenias. The gardenias’ sweet aroma pervades the airport.

Since the Columbus reporters want to question Prabhupada, we arrange a special seat for him at the end of a corridor, where he speaks briefly.

“Are you a Buddhist?” one very confused reporter asks.

Prabhupada smiles kindly. “Buddhist and Mayavadi philosophies externally deny the existence of God and are atheistic,” he explains. “One says there is no God, another says that He is impersonal, but we Vaishnavas, devotees of Krishna, are directly personal. We serve the person Krishna, and by this we are eternal gainers. Service, as you know, is not a very pleasant thing in this world, but service to Krishna is different. If you render Him service, you’ll be satisfied, Krishna will be satisfied, everyone will be satisfied.”

“So, just who is this Krishna?” another reporter asks.

“Come to our temple and find out,” Prabhupada says, then adds that by Krishna, “We refer to God, Bhagavan, the Supreme Person.”

Then Prabhupada holds up a new copy of Bhagavad-gita As It Is.

“This Bhagavad-gita is most important. You should read it carefully. In it, God is speaking about Himself. We don’t have to speculate or read hundreds of books. If we understand just this one book, or just one sloka, one verse, we understand everything. Give up your mental speculation. The laws of nature are kicking you at every moment, and you should know it. You are not the unlimited Supreme Person. Just try to hear about the Supreme from the right source.”

With this, Prabhupada ends his brief arrival statement. We leave the airport and go directly to the temple on Twentieth Avenue.

Students overflow the house and stand on the sidewalk and lawn. Now, at last, our identity is well known to neighbors.

“Yes, a very nice building,” he says, inspecting even the upstairs bedrooms. “So because you are sincere, Krishna is giving you all facilities. The first requirement is sincerity to become the Lord’s servant. We don’t have to go far. Once qualified, we can talk to the Lord from within. The Lord is beyond our sensual perception, but He can reveal Himself to us. If you are a true lover of Godhead, you see God everywhere, in your heart and also on the outside. But the Lord reveals Himself only through this bhakti-yoga process.

Before kirtan, Prabhupada takes a short rest. When he enters the kirtan room, the chanting and dancing stop. We offer obeisances.

“Go on with kirtan,” he says, and we resume chanting.

We open the side windows so that students standing outside can see in. Since we are all packed tightly in the rooms, it begins getting hot. Hrishikesh fans Prabhupada with a peacock feather fan. The students stare at Prabhupada and his devotees, and strain to hear.

Prabhupada announces that his subject is Vedanta, the ultimate goal of knowledge. Everyone in a university is seeking knowledge of some kind. So where does all knowledge finally lead?

Citing Srimad-Bhagavatam, he points out that true knowledge is lost because of the degradation of this age of Kali.

“In previous ages, men were far more advanced,” he says. “Arjuna, for instance. Bhagavad-gita was spoken on a battlefield, so you can just imagine how much time Arjuna spent studying it. At the utmost, Lord Krishna spoke the seven hundred verses in an hour, but in this brief period Arjuna understood it all. We can hardly imagine how great a man Arjuna was. Now we are so fallen that so-called great scholars cannot understand Bhagavad-gita, even after many years of study. Arjuna was not a brahmin; he was a military man. And formerly, Vedic knowledge was shruti, spoken, not written down because the brahmacharis had such fine memories that they could remember everything on first hearing.”

Some students, who are writing down notes out of habit, laugh good naturedly.

“What of tape recorders?” someone asks.

“Of course,” Prabhupada laughs, “you have now become so advanced that you need these modern amenities. But formerly, there was no such need. The recording device was already there in the finely developed tissues of the brain. But such powers were cultivated by celibacy and sense control.”

“All religions accept the fact that God is great,” he continues, “but they do not know to what extent. That information is given in these vast literatures. In any case, the test of first-class religion is love of God.”

“But aren’t we already connected to God?” a student asks.

“Certainly. Without connection with God, we cannot even sit here. God’s energies are working, and at any moment the whole material manifestation may be vanquished. It is by the mercy of God that we are living at all.”

The students listen intently. They have never before heard anyone speak with such urgency and authority about God. Prabhupada seems even stronger than in 1966. He speaks with force, emphasizing certain words, meeting the philosophical issues head on. Immediately asserting the absolute authority of the Vedas, he points out that Vedic literature is not concerned with just planet earth but with all the planets in the universe.

“Lord Krishna spoke this Bhagavad-gita to the sun god many millions of years ago,” he says. “What Lord Krishna spoke is perfectly clear. We do not need the interpretations of some mundane scholar.“

In conclusion, Prabhupada humbly submits his role in the transmission of knowledge.

“Our mission is to deliver this Bhagavad-gita as it is, just as the postman delivers your letter as it is, and both the good news and bad news are for you. The postman’s job is to deliver what is sent, and our mission is to present Krishna’s message as it is. Thank you very much.”

After the lecture, we serve vegetable kachoris with raisin chutney and fill styrofoam cups with nectar—sweet, rose-scented yogurt—a preparation Prabhupada has just taught Kirtanananda.

In the evening, Prabhupada takes hot milk in his room. All the devotees come in for an informal darshan —Kirtanananda, Pradyumna, Ranandhir, Hrishikesh, Paramananda, Satyabhama, Arundhuti, Vamandev, Shamadasi, Nara-narayana, Purushshottam, Devananda, and others. Present also is a young man called Luke from Akron, and a Puerto Rican named Carlos from New York, both due to take initiation, both now chanting their beads and pressing close to Prabhupada’s desk.

The carpenter Vamandev raises the first question: “What of these new gurus who claim to be God?”

“And what if I say that I am President Nixon?” Prabhupada challenges. “Would you accept me? just tell me why not?”

“You don’t have the characteristics,” Vamandev says.

“That means you are not insane,” Prabhupada says approvingly. “But if I say I am God and you accept me, can you begin to imagine such insanity? Double insanity. One man claims that he’s God, and the other man accepts him to be God.

“Are we not all one?” Carlos asks.

“That is a different thing. Are you one with President Nixon?”

“Yes. He’s a human being.”

“That may be. As human beings, you both have so much in common, but still you cannot say that you are President Nixon. In so many qualities, we are one with God, but we aren’t God. Those who do not know how great God is try to claim His greatness. This is insanity, is it not?”

“Yes.”

“Insanity means forgetting God. Forgetting God means material consciousness, maya. When a man is insane, his condition is considered abnormal. Sanity is his normal condition. Maya is an abnormal departure from our original Krishna consciousness. Actually, maya means having no existence. It just appears to be there. In maya, we falsely think that we are independent. But really, who’s independent? Can anyone claim independence?”

“No more than proprietorship”‘ Kirtanananda says.

“Achha!” Prabhupada smiles. “So these are all false claims, hallucinations. Everyone is thinking, ‘Oh. I have so many problems.’ But the only problem is, ‘How can I best serve Krishna?’ And Krishna is so kind that He says, ‘Just chant Hare Krishna.’ That’s all.”

There’s a moment’s reflective silence, finally broken by Luke, one of the boys awaiting initiation. Luke seems a big talker, big speculator, but is basically a simple farmboy.

“The Buddha’s teachings are very similar to Bhagavad-gita,” he says.

Prabhupada looks at him squarely, calmly. “Do you follow Buddha?” he asks.

Luke hesitates, surprised to have the subject bounce back.

“Well… no,” he admits.

“You simply talk of him?” he explodes suddenly, as if just talking of Buddha were some terrible outrage.

All eyes turn to Luke, who now seems very startled. Like all of us, he is receiving Prabhupada’s mercy without realizing it.

“If you are serious about Buddha, then meditate,” Prabhupada says sternly. “But you are not serious. You simply talk.”

Luke glances at the floor, his face now red with embarrassment.

“Do something!” Prabhupada shouts so loudly that we all jump. “Whether you follow Christ or Buddha or Krishna, it doesn’t matter! Don’t just sit and talk! Follow someone! Lord Buddha is very nice. If you like, you can become a Buddhist priest and meditate. Go do it. But that is your problem. You don’t do anything. You talk much. Just do something and do it perfectly.”

As always, Prabhupada hits the mark. That is indeed our dilemma: to do, or not to do. Inactivity, the bane of armchair speculators.

At nine, Kirtanananda serves hot milk and sliced apples. Prabhupada happily mentions a priest with whom he chatted en route from Hawaii to Los Angeles.

“On the airplane, this Catholic priest told me, ‘Swamiji, your disciples have such shining faces. “Yes,’ I replied, ‘they are making spiritual progress.’ Krishna is the most pure. If you are impure, how can you approach purity? Tapasya, penance, is required. We voluntarily accept some suffering for the sake of transcendental realization. Is it not worth it?”

At four in the morning, there is an aratik In Prabhupada’s room before his Radha-Krishna Deities. Purushottam is the pujari. All the initiated disciples attend and chant the aratik mantras. After aratik, we leave Prabhupada alone to continue translations of Srimad-Bhagavatam on his dictaphone.

Shortly after dawn, we drive him to the banks of the Olentangy River, only a few minutes away, and he takes a brisk, thirty minute walk. From time to time, he stops to comment on trees or newly blossomed May flowers. Then he returns to the temple for prasadam and rest.

At ten, we drive to the Student Union for a meeting with the university’s Indian Association. We have a rousing kirtan, and the Indians partake timidly. Afterwards, they garland Prabhupada.

“We have heard so much of your work, Swamiji,” President Sanyal says. “And we so appreciate your Bhagavad-gita.”

The members of the association are wealthy, family centered, conservative, and professional. They have left India for technical training, or for a better paying job, or both.

Prabhupada’s talk is strong and pointed. It is clear that he very much wants his fellow nationals to help him. Describing ISKCON’s humble beginnings in New York, he points to the founding of twenty temples in less than three years.

“Many Indian students take this chanting and dancing as something trifling,” he says. “That is because they are imitating and trying to advance in technology like Americans. Indians are suffering because they are by nature Krishna conscious. They are not fit to imitate the West technologically.

“And what has India offered the West? Cheaters offering yoga methods not intended for this age. Maybe one or two people can understand Vedanta or practise hatha-yoga, but not the majority.

“India is the land of tapasya, penance, but we are forgetting that. Now we are trying to make it a land of technology. It is surprising that the land of Dharma has fallen so low. Of course, it is not just India. In this age, the entire universe is degraded.”

At the conclusion of the lecture, Prabhupada asks for questions, and one elderly gentleman enquires about the “reported existence of a New Vrindaban.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada says proudly. “We now not only have a New Vrindaban in West Virginia but also a New Jagannatha Puri in San Francisco. Americans have imported so many new cities, so why not New Vrindaban?” Prabhupada laughs, and the Indians smile appreciatively. “So, please now come forward,” he challenges them, “and join this movement. You Indians especially should help New Vrindaban. Just as Lord Krishna is the supreme worshipable Deity, His dham, Vrindaban, is also worshipable. Now we want to make a replica Vrindaban in the West and live a simple Krishna conscious life with cow protection and agriculture. So please join us.”

After returning to the temple, Prabhupada is so enlivened that instead of taking rest, he chants bhajans and plays harmonium in his room. I set up the tape recorder and accompany him with cymbals.

“Softly,” he says, playing elaborate cadenzas on the harmonium and chanting Jiv Jago” in an exotic, minor key, his voice impassioned and pleading. He soon becomes lost in his singing, his voice rising and falling like waves crashing on rocks and sands, the harmonium chords pulling the spent waters back to the basic theme, then letting them flow again, to seek the shore.

There is no hurry. His eyes are closed, his brows intently knit in concentration. His fingers press the keys firmly, precisely.

“Jiv jago, jiv jago, gaurachanda bole kota nidra jao maya-pisacira kole.”

He does not strive for some musical effect, but every note is marvelously correct, every vocal nuance colored just the right shade, effectively, masterfully, spontaneously.

“Lord Chaitanya is asking all living entities to wake up to Krishna consciousness.” he explains when the song is over. Jiv means the living entity, and jago means ‘wake up!’ So Bhaktivinode Thakur has written, ‘Wake up! How long will you go on sleeping in the lap of the witch Maya? In your mother’s womb, you promised to cultivate Krishna consciousness during this life, but you’ve forgotten everything under the spell of the illusory energy.’ In the womb, we suffer so severely that we pray to God for release, but once in the world, we forget. Therefore, jiv jago —wake up!”

When Prabhupada finishes chanting, Kirtanananda announces that Allen Ginsberg has just phoned.

“He’s in Columbus now,” he says. “He wonders when it’s best to visit.”

“Anytime,” Prabhupada says. “He can come now.”

“I’ll tell him this evening,” Kirtanananda says.

“Achha! We are always ready to talk of Krishna.”

And with relentless energy, Prabhupada takes up the dictaphone again. We all move quietly about the house, hearing his voice with satisfaction, knowing that he is presenting the greatest literatures to a world desperately needing them.

End of Chapter 16

Pasted with permission from; http://www.hansadutta.com/EXPLOSION/hkex16.html

1 Comment (+add yours?)